How can early monthly saving affect your later life?

14 Aug 2016

I have recently started to earn a paycheck that allows me to consider investing on a recurrent schedule. Since I have never really thought much about funds, or to be honest finance in general, it was difficult for me to visualize the benefits of early investments. Why not just wait a few more years until I make even more? How much of a difference will these years in between really make? I decided to look a bit closer using methods that make sense to me personally.

Before we begin, what this really boils down to is compound interest – how much return you get on your investment, as well as the return on the return on the investment. If you like me have never thought about this before it may sound a bit abstract, but it is fairly simple: you will not only make money on the initial investment, but also on all the money you have made on the investment up to a certain point.

How can we formalize this? The math would look something like this:

$c_1 = c_0(1 + p)^t$

Where $c_0$ is your initial investment, $t$ is the time span in a given unit, $p$ is the average interest rate over the time spans, and $c_1$ is the result of the compound interest over $t$ time. Nothing of this or the following is really ground breaking, but it has helped me appreciate the benefits of early saving and the cost of funds.

So let’s say that I would be interested in knowing how much an initial investment of €10,000 would rise given a yearly average rate of 8% over ten years.

Using Python, we can implement this as:

import pandas as pd

def cumulative_rate(start_amount, yearly_rate, months_saving):

monthly_rate = 1 + yearly_rate/12

return start_amount * (monthly_rate ** months_saving)

cumulative_rate(start_amount=10000,

yearly_rate=0.08,

months_saving=10*12)

22196.40234544711

So if I were to make an initial investment of €10,000 right now, it will have more than doubled in ten years. That’s a pretty nice number, but unfortunately most of us new on the job market don’t really have that amount of cash lying around, and it really doesn’t tell me anything about what monthly savings would mean in the long run.

Luckily, we can implement a variation of the function above to take recurrent saving into account. The function becomes a bit trickier, we have to make it recursive for this to work, but it is essentially the same idea as before.

def cumulative_rate_monthly_saving(start_amount,

yearly_rate,

months_saving,

monthly_saving):

if months_saving == 0:

return start_amount

monthly_rate = 1 + yearly_rate/12

return (cumulative_rate_monthly_saving(start_amount,

yearly_rate,

months_saving-1,

monthly_saving)

+ monthly_saving) * monthly_rate

Now what if I have €1,000 on the bank, and put away €100 monthly for ten years? How much will the interest rate affect the results?

saving_with_interest_rate = cumulative_rate_monthly_saving(1000, 0.08, 10*12, 100)

saving_without_interest_rate = cumulative_rate_monthly_saving(1000, 0, 10*12, 100)

print("Saving €100 monthly with 0% interest for 10 years: €{:,.0f}" \

.format(saving_without_interest_rate))

print("Saving €100 monthly with 8% interest for 10 years: €{:,.0f}" \

.format(saving_with_interest_rate))

Saving €100 monthly with 0% interest for 10 years: €13,000

Saving €100 monthly with 8% interest for 10 years: €20,636

Now that’s pretty motivating, but it still doesn’t tell me why I shouldn’t just spend the money now and save more later when I earn even more. How much would I make if I simply spent all my extra money on new stuff for the coming five years, and doubled the amount of monthly savings for five years thereafter?

first_five_years = cumulative_rate_monthly_saving(1000, 0.08, 10*12, 0)

last_five_years = cumulative_rate_monthly_saving(first_five_years, 0.08, 5*12, 200)

print("Saving €200 with 8% interest for 5 years: €{:,.0f}".format(last_five_years))

Saving €200 with 8% interest for 5 years: €18,100

So despite saving twice as much five years into the future, I would still have lost 12% of my return compared to saving the same amount of money but starting now. I guess I better start saving.

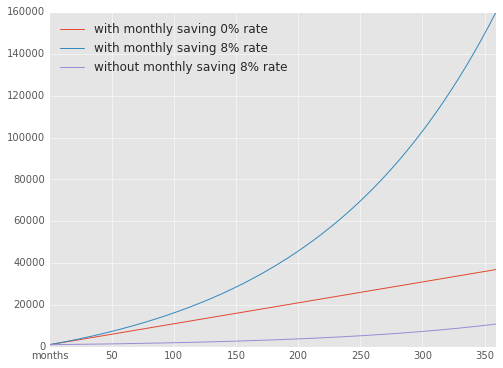

But hold on, why now now? I have no idea when I will need this money. What difference does it make if I start now compared to in another five years, if I don’t need it until I’m old and retired? Here’s where the compound part of the interest really displays its importance. Let’s plot the development of your funds for the coming twenty years, with and without savings, and with and without interest rate.

start_amount = 1000

yearly_rate = 0.08

months_saving = 30 * 12

monthly_saving = 100

with_saving = lambda months_saving: cumulative_rate_monthly_saving(start_amount,

yearly_rate,

months_saving,

monthly_saving)

without_saving = lambda months_saving: cumulative_rate_monthly_saving(start_amount,

yearly_rate,

months_saving,

0)

with_saving_no_rate = lambda months_saving: cumulative_rate_monthly_saving(start_amount,

0,

months_saving,

monthly_saving)

months = pd.Series(range(months_saving))

pd.DataFrame({'with monthly saving 8% rate': months.map(with_saving),

'without monthly saving 8% rate': months.map(without_saving),

'with monthly saving 0% rate': months.map(with_saving_no_rate)}) \

.rename(index={0: 'months'}, columns={0: 'USD'}) \

.plot()

Oh boy, it really takes off in the end, doesn’t it?

Alright, you convinced me. Now, what type of funds should I choose?

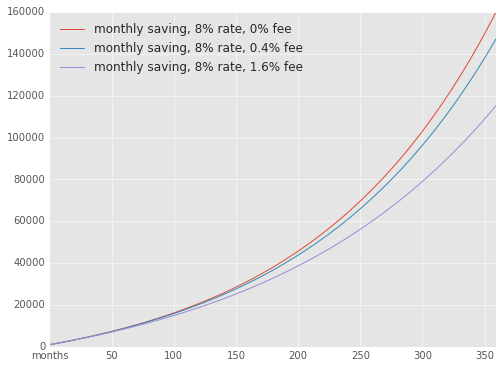

I’m really not the right person to give sound advice on this, but one thing that’s easy to miss is the cost of the fund. That is, how much of your profit goes to the bank? This is the big difference between actively maintained hedge funds, and passively maintained index funds.

I took a quick look on my bank’s website, and a management fee of 1.7% on the profit of hedge funds seem to be fairly representative. In contrast, the same fee for index funds is usually around 0.4%. Furthermore, my choice of bank has an index fund tied to the stock market index of the Stockholm stock exchange, with the peculiarity that it is completely free.

What kind of difference does this make in 30 years?

free_fund = 0

index_fund = 0.004

active_fund = 0.016

varying_fee = lambda months_saving, fee: cumulative_rate_monthly_saving(start_amount,

yearly_rate-fee,

months_saving,

monthly_saving)

free_saving = months.map(lambda n_months: varying_fee(n_months, fee=free_fund))

index_saving = months.map(lambda n_months: varying_fee(n_months, fee=index_fund))

hedge_saving = months.map(lambda n_months: varying_fee(n_months, fee=active_fund))

data = {'monthly saving, 8% rate, 0% fee': free_saving,

'monthly saving, 8% rate, 0.4% fee': index_saving,

'monthly saving, 8% rate, 1.6% fee': hedge_saving}

pd.DataFrame(data) \

.rename(index={0: 'months'}, columns={0: 'USD'}) \

.plot()

So by the time I am well within my fifties, I would have lost 20% of my profit on fees if I were to choose a hedge fund with the same rate of return.

But actively maintained hedge funds does sound a lot nicer, doesn’t it? And shouldn’t the active part make the return a lot higher compared to index funds? Well, there seem to be very little pointing to the fact that hedge funds perform better, and people a lot smarter than me agree with this sentiment.

I think I’m sticking with index funds for now, until proven otherwise.

Make your scientific Python 3 code reproducible by deterministic hashing

03 Jan 2016

As of Python 3.3, the built in hash function is randomized by default – for very good reasons! In short, having a deterministic hash function in production code is quite a security risk. We can see the effect of a randomized hash function by outputting the content of a set on multiple runs:

python -c "print(set(['A','B','C']))"

{'A', 'C', 'B'}

python -c "print(set(['A','B','C']))"

{'B', 'C', 'A'}

For scientific code, though, this could potentially be a problem. Since we want to make sure our work is as reproducible as possible, any stochastic elements will potentially make it difficult to regenerate previous experimental results.

As an example, I have some code that outputs a dictionary of features in the following format:

Number=Sing|Definite=Ind|Gender=Com|Case=Nom

The problem appears whenever I rerun the output and want to see if any differences arise between runs. Since the order of the dictionary output is determined by the hashing of the original keys, I cannot use e.g. git diff to compare the previous commited output with the current one.

If you have complete control and knowledge of your environment, your best bet is to either use OrderedDict and its counterparts whenever the sorting order cannot be assumed, or to simply sort the items of your dictionary ahead of iteration.

Most of the time, we don’t have this luxury. I quite often rely upon separate libraries and scripts for my work that I cannot in good faith start modifying. Instead, we could ahead of running the experiments set the environment variable PYTHONHASHSEED to an integer value.

export PYTHONHASHSEED=0

python run_experiment.py

At last, I want to emphasize: this should only be done with the purpose of having a non-random ordering of sets and dictionaries! If you actually want a deterministic hash value of e.g. a string, you should almost always use hashlib.